Overview of Civil Commitment Experiences and Grievance Policies

Several pieces of legislation in Illinois focus on civil commitment:

Civil commitment in Illinois is targeted toward individuals labeled as “Sexually Dangerous Persons” and “Sexually Violent Persons.” These labels are applied based on psychological evaluations conducted by court-appointed psychologists and psychiatrists. Here are the legal definitions of these labels, taken from the Illinois Sexually Violent Persons Commitment Act and the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act:

“Sexually Dangerous Persons” are defined in the law as “All persons suffering from a mental disorder, which mental disorder has existed for a period of not less than one year, immediately prior to the filing of the petition hereinafter provided for, coupled with criminal propensities to the commission of sex offenses, and who have demonstrated propensities toward acts of sexual assault or acts of sexual molestation of children.”

A “Sexually Violent Person” is defined in the law as “a person who has been convicted of a sexually violent offense, has been adjudicated delinquent for a sexually violent offense, or has been found not guilty of a sexually violent offense by reason of insanity and who is dangerous because he or she suffers from a mental disorder that makes it substantially probable that the person will engage in acts of sexual violence.”

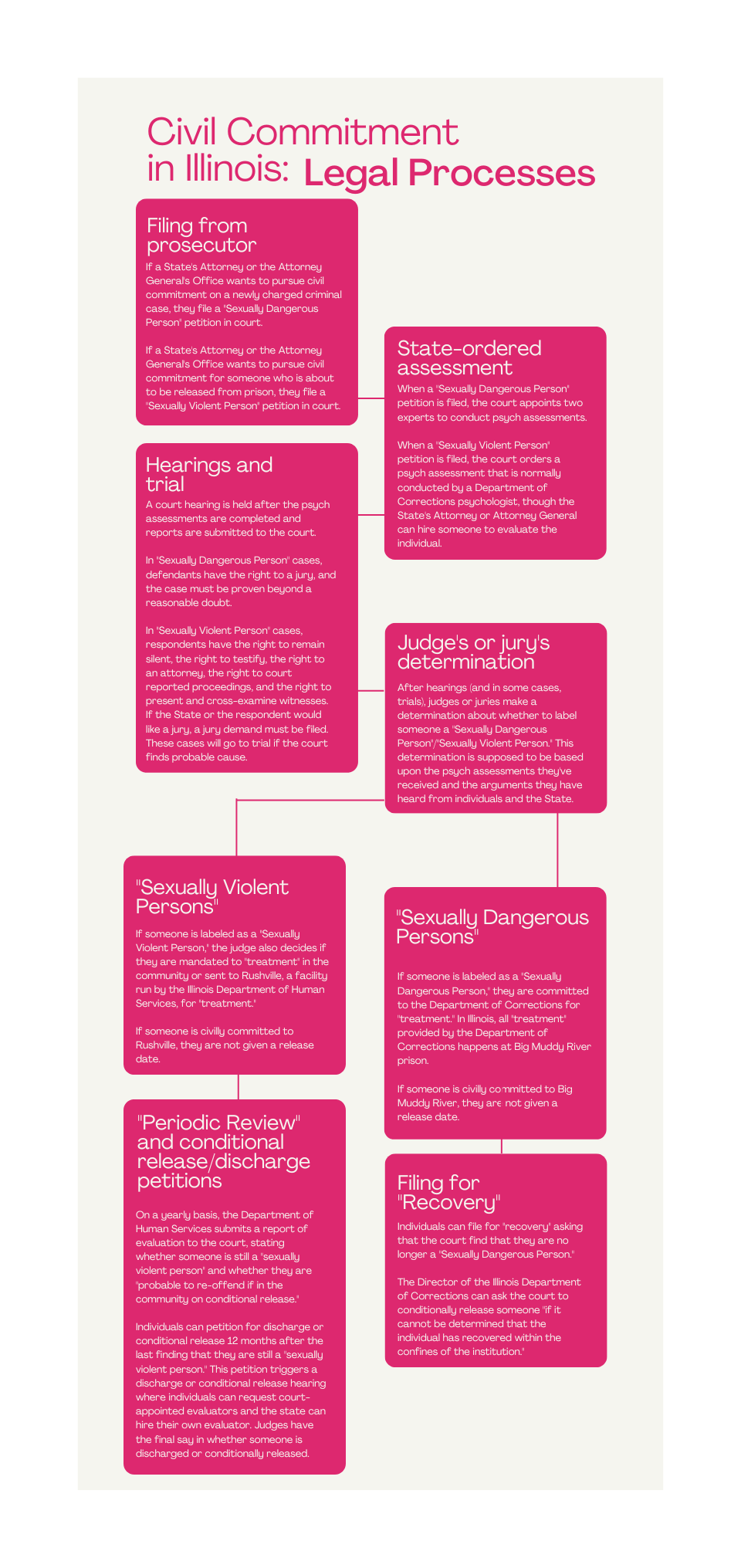

An overview from the Illinois Sex Offender Management Board website explains civil commitment in more detail. In Illinois, civil commitment begins after a prosecutor (from the State’s Attorney’s Office or Attorney General’s Office) requests a psychological evaluation to designate someone a “Sexually Dangerous Person.” After two “experts” assess an individual, there is a hearing in court where the prosecution argues for this label and an individual is able to defend against the label, all based on the reports of these “experts.” After a hearing, a judge in criminal court may decide to label someone a “Sexually Dangerous Person.” Civil commitment involves sending this person to the Illinois Department of Corrections for “sex offender treatment.” Individuals who are civilly committed under this statute are sent to Big Muddy River prison. Although individuals can file for Recovery asking the court to determine that they are no longer a “Sexually Dangerous Person,” the Illinois DOC can also ask the court to conditionally release someone “if it cannot be determined that the defendant has recovered within the confines of the institution.”

Another instance of civil commitment begins when someone is labeled a “Sexually Violent Person.” In this situation, the State Attorney’s Office or Attorney General’s Office files a petition to commit someone to the Department of Human Services after they have already served their complete sentence in a Department of Corrections prison. Similar to hearings for “Sexually Dangerous Persons,” there are hearings for “Sexually Violent Persons” when a petition for commitment has been filed. The hearing rests on the results of a psychological evaluation, often completed by the Illinois Department of Corrections staff psychologist or someone hired by the prosecutor. If a judge designates someone as a “Sexually Violent Person,” they are civilly committed to Rushville, a detention center run by the Illinois Department of Human Services. This effectively extends the individual’s term of incarceration indefinitely.

Once committed, individuals have very few mechanisms to register grievances or concerns with their conditions of confinement. One resident of Rushville, Matt, has shared letters and documents that highlight details about the grievance and pre-grievance (“attempt to resolve”) processes as well as the “points” system of currency and punishments in place at Rushville. In the grievances Matt has shared, the grievance responses repeatedly discount Matt’s complaints.

In response to the lack of attention on issues within facilities, individuals detained at Rushville have created a newsletter that documents their experiences. In a December 2017 newsletter, one anonymous individual voiced their concerns in an open letter directed to a newly-hired “security director.” The letter reflects the realities of confinement at Rushville, including dangerous bunk beds, staff who antaognize them, and food that makes them lethargic. The letter asks: “What will you do? Will you come in and like most supervisors, be more worried about being ‘friends’ with the staff as opposed to making them treat us like human beings?”

This exhibit curated from the archive is comprised of 25 newsletters from the residents of Rushville, Illinois’s Department of Human Services-run facility for confining individuals labeled as “Sexually Violent Persons.” Their newsletter, The First Amendment, touches upon a number of issues and grievances while also showcasing residents’ creativity and writing.